Sergio Zavoli is familiar with my painting. He is also familiar with other aspects of my life. So am I with his life and his commitments as a journalist, a writer and a poet.

We share several interests, even political, and we have still many curiosities to cultivate. Sergio sometimes comes to my atelier and we talk about matters which are not always concerned with cultural or existential aspects; on the contrary, we often speak about trivial and amusing things. But when we have to face something peculiar -not to say difficult, as I should say - we exchange a quantity of ideas, fixing here and there our cornerstones, to fix our thoughts, taking the liberty to reconsider similarities and diversities, approvals and dissents. We have been recently concerned, rather obstinately, with... illustrations! And explains:

was committed to a new work, somehow risky! And now that we have the opportunity, we decided to imitate ourselves by reconstructing, as far as memory and some pages of notes can help us, the questions and answers.

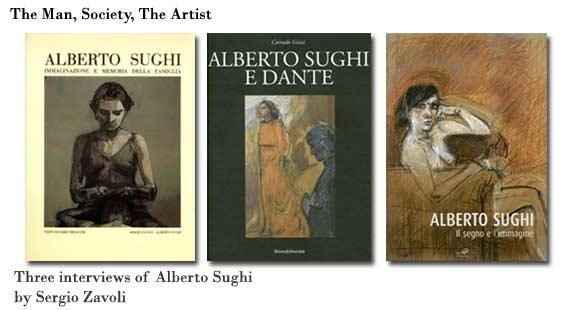

Alberto Sughi.

Alberto Sughi, Portrait of Sergio Zavoli,

Oil on canvas, 100x120cm, 2003

SZ You accepted a short time ago that the tables dedicated to the Promessi Sposi (The betrothed) were called, on the front page, 'Alberto Sughi's Illustrations'. I wondered how a natural enemy of illustrations has accepted - for the first time, as far as know - this definition. Why?

AS I still have the opinion that the specific characteristic of painting is not arguing or illustrating but rather, or exclusively, showing. On the other hand, I couldn't suggest a word to indicate in a more appropriate way the works accompanying this literary work. When you use the word tables you mean illustrating tables. The word illustration has perhaps a wider meaning.

SZ Illustrations are not always something embellishing, didactic, arbitrary, servile...

AS Absolutely not, just think about the drawings of Dante made by Botticelli, Luca Signorelli, even by William Blake and Johan Heinrich Fussli's memorable water-colour paintings on the cantos of Hell: such masterpieces may be appreciated notwithstanding their relationship with Dante's work.

SZ The acceptance of the traditional representation of Dante's face is a way, I suppose, not to superimpose your work on an agreed compulsory nature of the model. Why, then, do you place it in modern times? Do you leave itin and, at the same time, take it out of its time?

AS I think that there was not other choice, the iconography of Dante's face is so deeply rooted in our imagination that nobody has ever dared to go too far from it. His representation, stubbornly suggested by an archetype, eventually becomes a sort of portrait out of time.

SZ How is Dante's greatness expressed by images? Is it possible to give a plausible idea of it by simple illustrations? The experts of Dante's works dedicate to him huge works of reflection, exegesis and criticism:

where do you find, let's say, the compromise reconciling your creativity with the agreed essence of Dante's work?

AS If I had thought that, to make a series of paintings and drawings dedicated to La Vita Nuova, I should have reached the academic level where the Dante's work is placed, I would not have started the work. No, was on the contrary determined not to move too far from my painting and to try to find, within my research, the instruments to offer a possible visual reading. Eliot says: from reading Dante there often arises the "problem of the gap between tasting and understanding. What is surprising in Dante's poetry is, in a certain sense, that it is easy to read. It's evidence (positive evidence) that real poetry may communicate before letting itself be understood". One of the aspects of Dante's greatness may probably lie in the relationship between form and content. Starting from this premise, I kept to the magic, the beauty, the allegorical force of the sonnets of La Vita Nuova even if, in this case, I felt I was not fully penetrating their meaning. On the other hand I do not believe - I am not an expert of Dante's works - I was obliged to put my work as a painter in connection with the enormous and still unperfected critical exegesis on Dante's works.

SZ You are a sort of Virgil who takes him to see our world of today: the only possibility is to imagine that he looks at us, unseen, obviously silent. Is this representation, so discreet and laconic, a cultural scruple, professional prudence, complicity with the project or simply the highest transgression you could allow yourself?

AS I just thought that an important element, stored at the bottom of our conscience, determining our identity as Italians, refers to Dante: this was the reason that suggested to me a cycle of 7 works, the same number as those directly inspired by La Vita Nuova, that I wanted to entitle "Dante amongst us".

SZ At the times when much was said about a film dedicated to the Divine Comedy - and Bergman, Kurosawa, Fellini were each indicated as the director of a part - against all expectations Fellini expressed that he wanted to be engaged not for Purgatory or Hell, but for Paradise, the refined and pure form of truth, love, harmony. I had the opportunity to ask him why. He answered me and said that, of all the extremes, the conciliation of opposite elements is instinctively the most appropriate to our nature: Good and Evil, Love and Hate, Art and Kaos, Life and Death and so on. He added: "The great epic poetry of God". You do not have eschatological impulses - not even in Federico's laic and almost esoteric way -, after this first time, are you ready to engage in the Comedy?

AS If I were a painter of some centuries ago (today's film directors play the part once played by painters) I might reply like Fellini and I share the contents of his reasoning. But these problems occupy a shielded place in the thoughts of a painter of the present time: in a certain sense all modern painting, including figurative painting, has become "abstract" and its meaning often seems ambiguous and arbitrary. But just thanks to its ambiguity and even to its arbitrary aspect, modern painting reached the most convincing results (the ancient fiction of painting died, painting did not). The Divine Comedy? Maybe the most enigmatic work, but La Vita Nuova is the most difficult to represent.

SZ Love is an archetype in Dante's work, it is an absolute, any direction it takes. How did you differentiate the illustrations to represent the highest topic in an appropriate way? What skills did you employ?

AS Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare (So gentle and so pure appears): I started from this sonnet. This choice may seem obvious:

but Dante's love for Beatrice is La Vita Nuova's theme. A platonic love, unreciprocated but sublimated. As Beatrice's character remains rather mysterious, I took the liberty of thinking that Dante, while telling us about this overwhelming and unhappy love, spoke about something else. I drew a dignified and light of step young woman. I realized, while working, that it was necessary to attribute to the image a strong allegorical meaning in order to give it expressive force: the young woman crossing the space of the painting cannot only be Beatrice's portrait, but also the metaphor of philosophy, a means to reach truth.

SZ Some "courage" is recognized in the artists who work at the great models of the human creativity. What kind of courage is it? Would you call it so, that is to say courage? How would you call it, as an alternative?

AS It would be perhaps more difficult to face the authors of art and culture who occupy places smaller then those we reserve to the highest representatives. These great protagonists left a legacy that, perhaps in different ways and according to interpretations that are not always shared, marked our cultural formation. It is true that dealing with the classics leads us to consider how far we went from the universal language and thought. It may be very difficult to reach, serenely, this consideration, which seems to humiliate our presumption.

SZ You are one of the most renowned, and I would add "historical" painters of our current erratic, contradictory, controversial contemporary times. I mean that you are an artist of your time too, who contributed to make history of some parts of it. Your existential realism, in this sense, paved the way. You are, after all, the result of your being a witness besides being a protagonist. How did you face, without considering the specific philological aspect, Dante's texture? How could you remain an author, moreover with your peculiarities, in front of a matter that requested to be interpreted in all that series of combinations: expressive and conceptual, existential and historic, moral and religious?

AS We have already partly said it: I am not a philologist and I did not approach Dantes's poetry using a method unknown to me. I would have been forced to take for good all the explanations, often in disagreement, given by the experts. I kept my self to figurative reading with the tools of my lob, with commitment and passion. And also, I believe I can say so, with a certain humility.

S.Zavoli, Roma, Maggio 2003

(Sergio Zavoli, was born in Rimini in 1923, he is a journalist, writer and the former Chairman of the Italian National Broadcaster, RAI