| albertosughi.com |

The Drawing and the Image, Sergio Zavoli interviews Alberto Sughi

|

||

| Sergio Zavoli I don’t suppose, Alberto, that you have ever suffered from the syndrome of Leonardo. I also doubt that you have ever painted from a model, a manikin, or from some anatomical text, with its spectacular branching of veins on a hand or a leaf. I believe, in fact, that your sign was created outside the context of any academic rules. Indeed, it is quite extraordinary that you are not the product of any school, discipline, criterion, or method. Indeed, from the collection of your drawings, even the most extemporaneous - even those in which you are practising, as if in a game or pastime, perhaps while on the phone - the foremost of your talents emerges, your line, to which you entrust, as in writing to the writer, the structure of your art. But is it always essential to have a sign that - inspiring everything that develops on the canvas - is essential to its structure, if not the actual essence of the painting? Can you be a creator of images without this talent a priori? Alberto Sughi Your line of thought is intriguing. Starting from a problem that certainly concerns me, you ask me and, ultimately, yourself, questions that refer to a more general issue, i.e. whether the artist is the natural child of his talent, capable of producing complex and extraordinary works while remaining unaware of the reasons and procedures that have created them. Does the sign support the artist only at the moment of inspiration, or of intuition, not analysed rationally, and without which the painting, to be resolved pictorially, would not exist? Or is the artist a figure who cultivates and refines his sign, while certainly considering it an essential tool for his art, but not assigning it a founding or fundamental role, and does it therefore remain distinct from the work as a whole? I believe that an artist does not renounce any freedom, even when it seems that his sign is imposing itself on his work, but, in fact, analyses and transforms it, gathering further experience and knowledge of it while following the general development of the work.

SZ Have you ever thought of using a different line, experimenting another type of "writing"? SZ What price have you paid, so to speak, for being such an excellent draughtsman? Anyway, it was immediately obvious that it made your painting clearly recognisable... SZ Why, contrary to what happened to you, were some of your fellow artists – I’m thinking particularly of Vespignani - rewarded for a sign that graphically “exhausted” the painting itself? SZ Any painting, then, is not separable from the sign in which it unfolds, and which it expresses. Even when the sign appears to be denied by its self-destruction, that is, by so-called informality, it frees itself from the painting? SZ Why has the sign, in itself, principally in itself, lent itself so often to the use that ideology has made of it? Perhaps because it corresponds to a simpler eloquence, it has greater figurative expression? SZ Does the insistence of a theme, and therefore of a sign, present in such a large part of your work - that is, the representation of the relationship between man and woman - belong to the "obsession with the subject", which Moravia described at the beginning of his career, when artists were questioning themselves on their role in life and society, ideology and politics, or is it something else? SZ The line, when it is pure and only drawn, is like a continuous fringe. It has no other means other than itself of adding and removing from the composition. The rest is made pictorially. Is it therefore fundamentally explanatory in nature? SZ Although most of your paintings contain a strong figurative element, there are those who insist on looking for assonances, interactions, atmospheres recalling other expressive art forms, which use different instruments, such as the cinema. The work of Antonioni, for example - founded upon the bourgeois, disturbing, and mutually inaccessible relations between people - or of Scola, like a socio-analyst who turns observation into introspection, between psychology and reality, poetry and documentary, or of Fellini, who was the first to call your art "an art of the image, both in the sense of the single frame and of the whole story", where the static and the dynamic, explanation and allusion, ambiguity and scandal exist in a continuum that never eludes the contrast between reality and dreaming, even privileging the idea that "imagination is the highest mode of thinking", as the great director loved to say when he was reproached for hiding behind symbolic "abstruseness", that was more or less psychoanalytical. I remember that, at Monteporzio, Federico "studied" you for a long time in the paintings at my house, and compared your works "to something filmic, like the cinema, in their creation from light". And here is my point: if all of this makes sense, and continues to exist, can you still say that your work is no longer living, that it has been expelled by its uselessness, made superfluous and debased by the huge abuse of images inflicted on our eyes every day, as if, in that monstrous incontinence, they were confused, and those produced by artists were becoming annihilated? SZ Luigi Cavallo has interpreted your paintings, arriving at the same conclusions as Fellini by a different route. He mentions the "theatricality of daily life" (Is it just a coincidence that one of your most important paintings is entitled "Theatre of Italy"?) as the key to the continual duplicity of existence. This - I think his reasoning can be summed up as follows - explains your sharp and painful predilection for atmospheres created between strangers and silent, stunned people, in other words, the accomplices of an existential conciseness, never judged, but observed, pitilessly, in their icy, even painless, detachment. What part of this interpretation of your work, which both Italian and foreign art critics compare to the expressive forms of Bacon, do you no longer find expresses the usefulness of painting? What judgement does it refer to? SZ It is incredible, in the sense that I find it hard to accept its profound reasoning, to imagine a painter, one of the most highly reputed figurative artists of our time, feeling that his own appreciation of his, let us call it, “artistic activism”, is lacking. It seems unnatural to imagine a threshold beyond which an artist, as renowned as you are, can discover a sort of ontological unbelonging of his own painting (in the sense of its increasing ineffectiveness) in the process of deciphering and representing a reality that should require, more than ever, the interpretation of art. I’ll ask you a group of questions, but perhaps there is really only one: where have you found the concrete reasons for your disenchantment? Which is the cost of this “drifting”, if I can call it this? What could redeem the task of the painter in such a rapid race against time towards the death of so many things, starting from the imagination and beauty, from philosophy and morality, from humanism and ethics? Does art no longer serve to tell us who we are? Is everything really so subservient to the so-called exact sciences, so much more detached and sad than that "science" which emanates from every judgement that art, including yours, declares every day? SZ That was a time when art was involved, fundamentally, in a general description of history and human destiny, while today’s art does not feel the same need to refer to it. This is because its answers can no longer keep pace with an increasingly fragmentary interpretation of the world, as we have been saying for a long time, pushed aside by the speed of new interpretative instruments provided by science and technology, and by politics and all the social sciences, starting from communication. SZ Carlo Bo wrote "Literature as life", which describes the highly creative development of humanistic culture in the period between the two last centuries. Today you could not write anything similar about the period covering the end of the 1900s and the beginning of the third millennium. I would like to ask you for your opinion about these aspects of the problem, although seen in different contexts, in the eyes a philosopher and of a moralist. With a touch of what could be alarm or resignation, Heidegger wrote: "In today's world everything now works. But this is exactly what risks becoming a problem: that everything functions, that this functioning creates further functioning, and that Man is increasingly torn apart and uprooted. This is already happening. By functioning so well we have already formed relationships - between each other, between reality and ourselves, between our imagination and ourselves – that are purely technical". This observation leads to another - similar, but arising from quite different reasoning, made by father Balducci, another sharp critic of our acclaimed modernity. Referring to the irresistible dominance of intelligence, he ends up fearing the thought that produces only another thought, and this thought yet another, so that at the end of a spiral of thought that only thinks of itself, there is no other reality to think about, since it has all, so to speak, already been thought about. "With the tragic conclusion that, in the end, there remains only a single reality and a single thought". In fact, science and technology have constructed a kind of planetary brain in which all artificial brains are interconnected. So, with all our electronic branches, algorithms and digital impulses, mankind risks becoming a technocrat, a mutant, searching for that other existence that virtuality is already able to represent: a “neo-reality” between the real and the fictitious that dominates our imagination more and more, producing our desires and conditioning our ideas. Where does your mistrust in the role of art stand in relation to a reality like this? What would serve to make it into a "scandal"? Is it perhaps already implicit, in your extraordinary maturity, which in itself, while increasingly better-classified, offers itself as a test of the increasing and general groundlessness of art? |

||

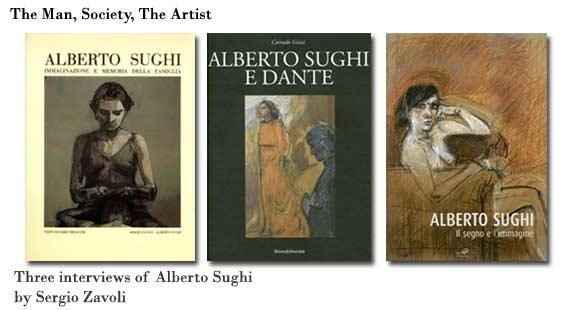

The Sign and the Image, Interview between Sergio Zavoli and Alberto Sughi is published in the retrospective exhibition catalogue of Alberto Sughi’s work, The Sign and the Image, presented by Giovanni Faccenda at the Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art of the City of Arezzo, from 14 April – 21 May, 2006.

|

||

| © 1997-2006 questa pagina e' esclusiva proprieta' di albertosughi.com La copia e distribuzione, anche parziale, richiede autorizzazione scritta di albertosughi.com Please ask albertosughi.com's permission before reproducing this page. |

||